Hidden Taxes Making Roth Conversions More Expensive

For many investors, Roth conversions are one of the best tools for managing long-term taxes. Moving money from a pre-tax IRA into a Roth IRA can reduce future required minimum distributions (RMDs), create more flexibility in retirement, and allow for tax-free growth for life.

But there’s a hidden trap that catches many people off guard, and it’s usually caught too late. When you factor in lost deductions or credits and other taxable assets, the effective tax rate on a Roth conversion can be far higher than the bracket you think you’re paying.

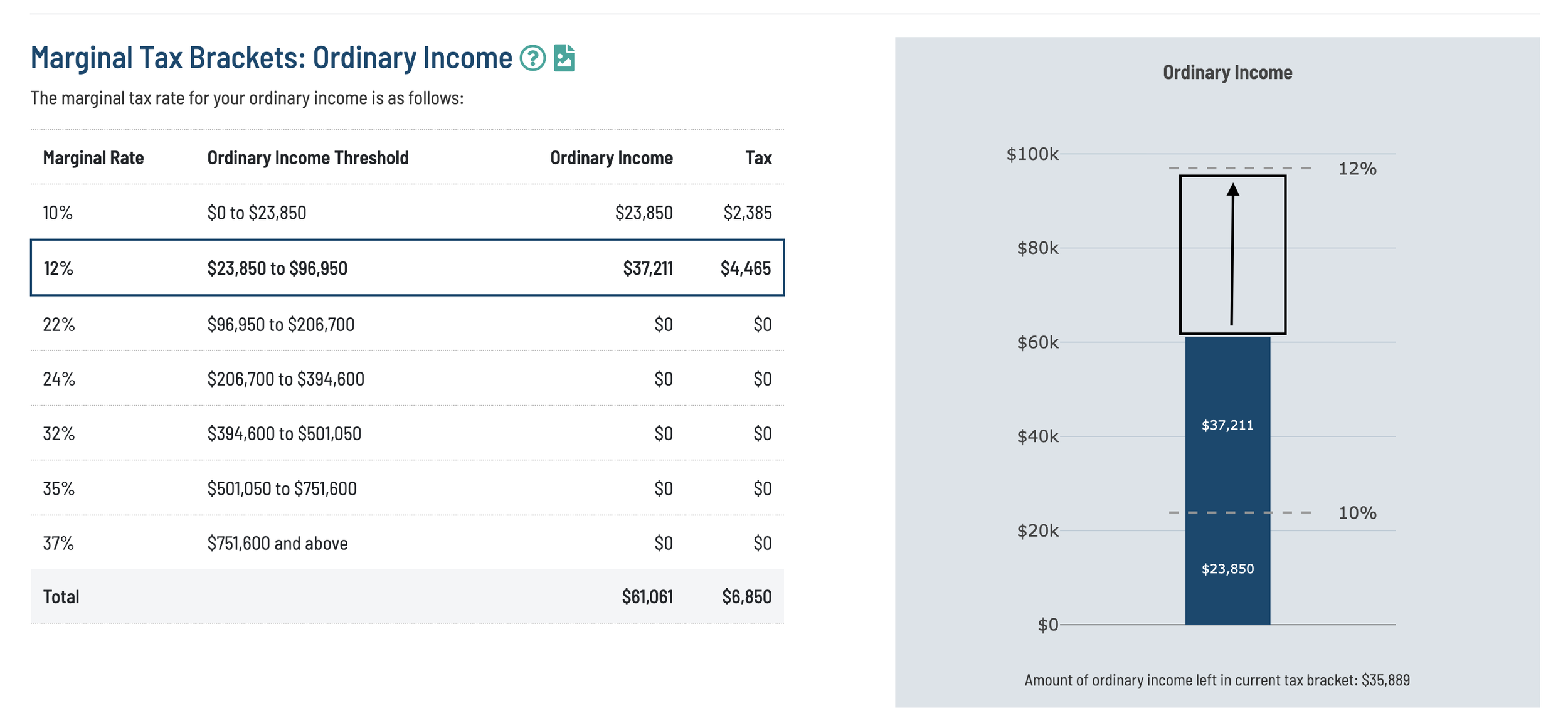

I was recently meeting with a client who, as an early retiree, had very little income beyond dividends and interest from non-retirement investments. Because of this, they had substantial room in the 12% tax bracket to do Roth conversions.

But the U.S. tax code isn’t as straightforward as the brackets suggest. When you have other sources of income, like qualified dividends or long-term capital gains, as this client had, converting more IRA dollars can cause those dollars to “stack” on top of your investment income and push part of it out of the 0% capital gains range.

Here’s what that means in practice --

Qualified dividends and long-term capital gains are taxed at 0% while your taxable income remains below about $96,700 (for married couples in 2025).

But as soon as your income, including the Roth conversion, crosses that line, the portion of dividends and gains above the threshold becomes taxed at 15%.

So, in addition to paying 12% on the converted dollars, you’ve also triggered new tax on income that was previously tax-free.

For this client, they would expect to have plenty of room in the 12% tax bracket to convert Roth money. Let’s say they wanted to do a $30,000 Roth Converison.

On paper, they expect to pay $3,600 (12% of $30,000).

But by doing the conversion, they push $30,000 of their qualified dividends above the 0% threshold.

That $30,000 is now taxed at 15%, creating an extra $4,500 of tax.

Their total tax bill rises from $3,600 to $8,100, an effective rate of 27% on the conversion. In more complex cases with Social Security taxation or state income taxes, the effective rate can easily climb into the 35+% range, even though the taxpayer thinks they’re in the 12% bracket.

That doesn’t mean you should avoid conversions. It just means they should be done with eyes wide open, ideally using tax projection software that models how conversions interact with your other income sources.

As with most things in tax planning, nuance matters.

Happy Planning,

Alex

This blog post is not advice. Please read disclaimers.